View: The Long Cycle | Above the Market

The Long Cycle | Above the Market

Barry Ritholz (of The Big Picture and a Sunday Business columnist at The Washington Post) recently contributed Investors’ 10 most common mistakes to The Washington Post Business Section quarterly investing section. It’s a commentary that he has been working on for a while — the ten topics are listed with links to longer discussions of each common mistake here. I created my own investing “checklist” (here) and a list on the most common behavioral biases (here) in response to Barry’s original list.

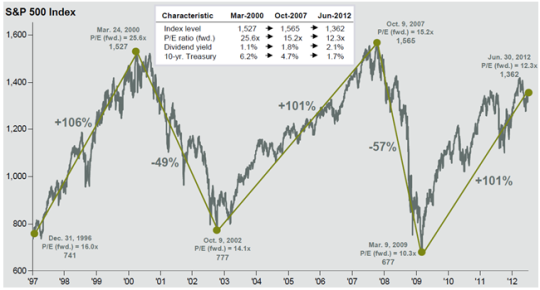

One common mistake that Barry mentions is “neglecting to pay attention to long secular cycles.” As Barry points out (and consistent with what I have arguing consistently for a long time), the current cycle is a secular bear market that began in 2000 and continues to this day, as illustrated below.

As he emphasizes, “[i]t is an investor’s job to preserve capital and manage risk during secular bear markets. During secular bull markets, maximizing returns are the top priority.” Today I am going to address the current long cycle in a bit of depth.

As he emphasizes, “[i]t is an investor’s job to preserve capital and manage risk during secular bear markets. During secular bull markets, maximizing returns are the top priority.” Today I am going to address the current long cycle in a bit of depth.

United States domestic equities have returned nearly 10% per year on average over the past 100 years. These historical returns compare to slightly above 5% for bonds and a risk-free (Treasury bill) rate of slightly more than 3.5%. In the long run, then, stocks are a great investment. Unfortunately, that long run may be much longer than you’ve got. As John Maynard Keynes famously put it, the market can stay irrational far longer than you can stay solvent. Indeed, for the first time ever, bonds have outperformed stocks over the past thirty years.

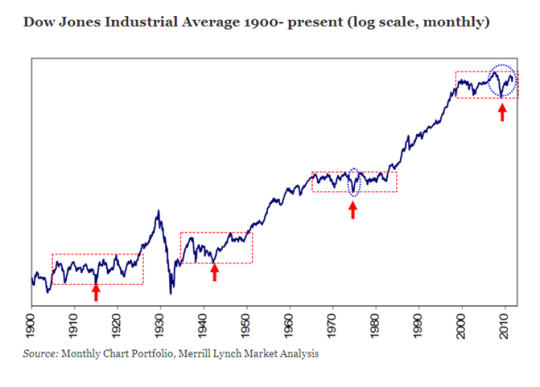

The roughly 100 years of market history we have suggests that markets experience alternating long periods of excellent price appreciation (secular bull markets) and long periods of price stagnation (secular bear markets). During secular bear markets, price movements tend to be sharp and may last for significant periods of time (see below).

However, there is little overall progress. On average, these cycles have each lasted about 17 years.

Investing in secular bull markets is relatively easy. Essentially all equity-focused portfolios perform well. Buy and hold works. Indexing works. Mutual funds work. Thus the common expression: never confuse genius and a bull market. But investing in secular bear markets, such as we have seen since roughly the turn of the century, is something else altogether. Since early 2000, markets in much of the developed world have essentially been flat to down. We are in a very difficult period. Nothing seems to work well or consistently. The market is short genius.

What’s going on?

There a number of measures by which one can examine the longer-term value (as opposed to the price) of the market. At certain times, typically when the economy is expanding and when inflation and interest rates are low, investors are willing to pay higher prices measured as a multiple of earnings for stocks. When the economy is struggling, when inflation and interest rates are high, or when deflation (negative inflation) occurs, investors will tend to pay lower prices and multiples. Obviously, this isn’t anything like an exact science. That said, most of these valuation measures clearly suggest that the market has been overvalued since well before 2000 and, despite the bursting of the tech bubble, remains overvalued today. Thus we have little reason to expect the current secular bear market to end anytime soon.

Stocks, like any product, can be overvalued, fairly valued, or undervalued. The goal with stocks should be – obviously – to sell the first category, hold the second and buy the third. Moreover, as the great Benjamin Graham famously phrased it, purchases should be made with a sufficient margin of safety – cheap enough, in other words – that the risk of loss is greatly limited. Graham and Dodd brought this idea into the value investing vernacular by first using the term in their classic treatise, Security Analysis. Put simply, they argued that investors should buy stocks that trade at significant discounts to value and developed screens that would yield these stocks. In fact, many of Graham’s screens in investment analysis (i.e., low P/E, stocks that trade at a discount on net working capital) are attempts to put the margin of safety into practice.

During the last secular bear market in the United States, from 1966-1982, earnings grew about 6.6% per year while P/Es declined 4.2%. Thus stock prices went up roughly 2.2% per year. The current secular bear market shows a similar picture, which largely explains why stocks are now trading pretty much where they were in 2000. Moreover, a secular bear market is full of cyclical (and often strong) bull and bear markets, as the chart above demonstrates. The 1966–1982 market had five of each. During cyclical bear markets, the benefits of earnings growth are wiped out by P/E compression. On those occasions when P/E compression comes during economic recession such that earnings do not grow (as in 2008-09), major market corrections occur.

There would be a great benefit, obviously, to be able to ascertain, in real time, when the great inflexion points between the secular bull and the secular bear occur. Unfortunately, doing so is exceedingly difficult, perhaps impossible. Current P/E10 levels and other valuation levels (e.g., DY10, Q, market cap:GDP) are still very high historically, but they could remain high for a considerable period of time. P/E levels are less high, but remain a bit suspect because so few companies are willing to expand and grow in the current (uncertain) environment. Thus the market appears overvalued, but that overvaluation could also continue for a long time.

The good news, however, is that these concerns about finding the inflexion point in the market from bear to bull are largely theoretical at this point because we are now – today – still clearly in the midst of a secular bear market. We needn’t decide now – today – when the next secular bull market will start. We need only determine how best to respond to the secular bear market which we currently suffer and how to profit from the cyclical and often volatile bull and bear market swings within it. This longer-range perspective allows investors to examine this market rather than merely try to escape it. The dangers posed by a secular bear market are real, but so are the opportunities.

During secular bear markets, an investor’s primary job is to preserve capital and manage risk in order to get to the next secular bull market. As noted above, during the 1970s secular bear market, there were tremendous price swings. For example, 1973-74 saw huge sell-offs, and the market was down about 55% — much like the recent financial crisis. In 1974-75, the market rallied roughly 60% higher, much like 2009-2010.

During secular bear markets, investment portfolios should be diversified across a range of investments that are diligently selected and carefully managed, especially ones that control risk first and only after risk is appropriately managed seek to enhance return. In particular, investors should not simply avoid the markets. Doing so would have meant the risk losing out on significant cyclical bull runs.

Portfolio performance evaluation is often put in relative terms (“We’re great because we lost less than our peers”), but families live in a world where real losses really matter, even if they may be less than someone else’s. Thus a careful investment approach, which uses a dual strategy of risk management and careful investment selection, makes especially good sense in secular bear markets. The current environment is an extremely difficult one. But careful management that recognizes where we are in the “long cycle” can allow for surprisingly good results overall.

Be the first to like this.

Comments

No comments yet.