“What was I like when I was little?”

I knew the answer to the question already. After all, I had asked it plenty of times before, and the response was comfortingly consistent.

“Oh, you were a gentle baby.”

As a child, I found great reassurance knowing that even during the phase of life that infantile amnesia prevented me from remembering, I was a gentle person. I’m not sure why it was so important, but all my life I have embraced gentleness as a crucial part of my identity, and I wanted to know from my mother that I had always been sweet-natured. I wished it for myself, and for her.

Growing up in the deep south, I was a happy child. I had plenty of friends, participated in the typical sequence of young-boy organized groups (Indian Guides, Cub Scouts, Webelos…….), and had plenty of hobbies to keep me entertained when I wasn’t at school.

I was always a smart kid, and I was known as such. It was my identity. But I wasn’t dork-smart. I was smart but still liked by other kids. I had found a pleasant balance.

Looking back, half out of the six years I spent in public elementary school were a complete waste of time. Three of the grades – first, fifth, and sixth – were taught by good teachers that really cared about the students. The other three grades – second, third, and fourth – I don’t even remember. It was that bad. I often wonder how much smarter or more able I would be today if I had experienced a quality education end-to-end. I’ll never know, of course, and I’m trying to provide my own children what I never had.

Although I didn’t win class election in the 5th grade (a story I chronicled some four years ago here on this blog), I did win the President’s race in the 6th grade. In the tiny universe that was mine, I was on top of the world. I had friends, “success” (as measured by a 12 year old, at least), good grades, and a loving family. I was a happy, lucky kid, and each day was a pleasure.

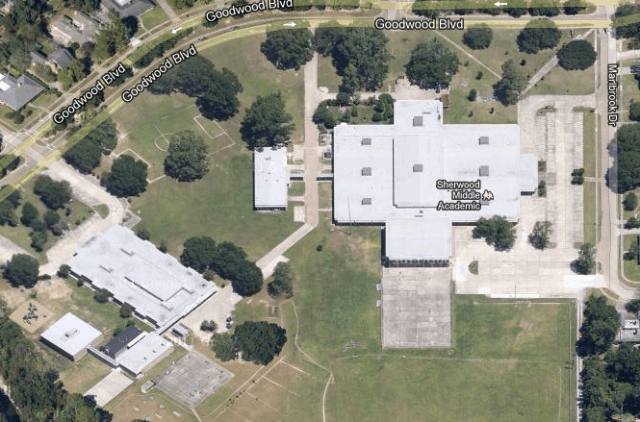

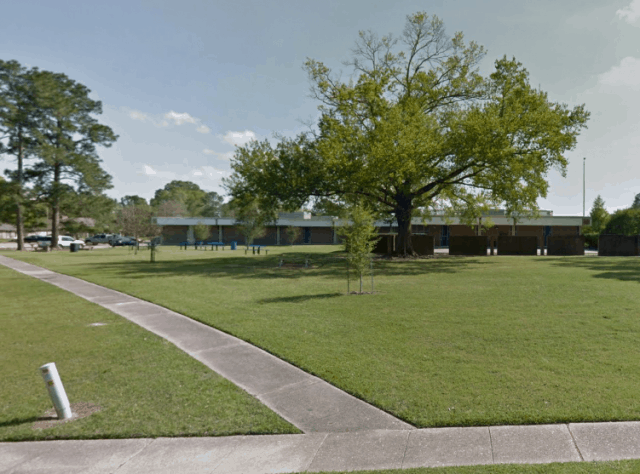

Something happened that summer, though. Something, in retrospect, that I considered terrible. Having graduated from Audubon Elementary School (shown at the left of the photo below), I was slated to go to Sherwood Junior High (shown on the right). It was obviously in the same neighborhood, but it would be an entirely different world for me.

Most of my friends were going to a different junior high, and Sherwood was going to be a bigger school. I wasn’t sure what to expect. When school started in late August, I would quickly find out.

I truly don’t remember what it was like starting there, but I can tell you, it was bad. I went from being the top dog (6th grade) to a nobody (the 7th). I knew hardly anyone, and the entire atmosphere of the place seemed different.

The friends I did have from my old school seemed to have changed overnight. In retrospect, I suppose puberty setting in was starting to alter personalities, and the kids entering junior high wanted to appear “grown-up.”

I didn’t, though. I liked being a kid, and I wanted to stay a kid. I felt very out of place, and it didn’t take long for the bullies – – a creature I’d never encountered in my life before – – to pick up on this and target me.

I’ll state here early on that whatever bullying I experienced as a child wasn’t severe in physical terms. Indeed, I wasn’t even hit – not even once – but as more than a few people have noticed in my adult life, I’m a sensitive soul, and it doesn’t take much to hurt me just with verbal taunts. And there were plenty of those.

The kinds of verbal put-downs were the same hackneyed crap that boys have been slinging at each other for decades. I was gay. I was a fag. I was a pussy. I was a dick. In their reptilian brains, the bullies sensed I was smart, and that simply wouldn’t do, so they’d resort to attacks against whatever manhood a 13 year old boy was supposed to muster.

The funny thing was that in the years I was assailed with all these put-downs (pretty much the 7th through 9th grades), there wasn’t anything about me that should have attracted attention. I wasn’t overly tall or short. I wasn’t especially ugly or handsome. I didn’t dress differently. I didn’t speak in a strange way. And I was about as heterosexual a fellow as there could be (although as an adult I realize they weren’t actually trying to make a reasoned assessment as to my sexual orientation). So it didn’t make sense that someone like me who should have blended into the scenery became a target.

Thus, school changed from something that I loved into something that I dreaded. And the three wasted years of elementary school now had a companion in the form of the 7th grade, as I would tack on yet another year that would be a complete waste of time.

I would wake up each morning with a knot in my stomach. I didn’t want to go. And the walk to the front door of that school became one of the longest walks I’d ever take. And it was a daily event.

One of the few friends I made also happened to be the first Chinese guy I had ever met in my life (this was suburban Louisiana, remember) – George Chang. He was very artistic, and that became his identifying characteristic (which was probably lucky, since the dickheads at the school would probably have otherwise targeted the fact he was Asian).

I admired him a lot, not only because he could draw great comics, but also because he transcended the taunting. People seemed to leave him alone. I wish I could have said the same of myself.

I tried so hard to fit in. I let my hair grow out, for one thing. I normally had a very conservative haircut, but in order to look like the others, I made my haircuts as infrequent as my mother would permit. And, when I did get a haircut, I did so on a Friday, just to give my hair the weekend to grow back a little. (This probably explains why, as an adult, my hair has stayed consistently short; there’s no way I’m going to return to the fakery of hair draped over my ears. That is so not me.)

After a while, I did manage to make a friend in my home room – Mike (I don’t remember his surname, but I remember his face). It was nice to have someone to talk to, even though I certainly didn’t act like my normal self, in an effort to fit in. I talked about whatever he wanted to talk about, and I didn’t let on anything resembling intelligence. I just wanted to be liked and included. I didn’t want to feel alone.

One Saturday, I invited him to see a new movie that had come out – Superman. So we watched it together, and my Dad came to pick us up. I excitedly told my father about the movie, which I had really enjoyed. And then I made a big mistake – – I told my Dad how Superman had flown around the Earth, exceeding the speed of light, making possible the reversal of time, and thus allowing him to rescue Lois Lane.

I had let it slip that I was smart. And I wouldn’t realize until Monday that this would matter to Mike.

When I came into homeroom on Monday morning, Mike wouldn’t say a word to me. I couldn’t understand it. He was stone-cold to me. I tried to talk to him to comprehend what was wrong, because I didn’t understand. He didn’t want anything to do with me anymore. And he wasn’t my friend for the rest of that year. I had killed a friendship just by being myself for a moment.

Gym, of course, was the worst. I never had an interest in athletics, and P.E. was the place where the jocks got to shine. Much worse, it was the place they got to abuse those who weren’t as good at sports.

P.E. – held every single school day – was the low point of every weekday. It became so hard to muddle through that I would leave little notes to myself in my locker, to be read after I got done with P.E., congratulating me on having made it through. It was a little game I played with myself to know that it would be over, and there would be a voice waiting tell me I had made it through another lousy day.

Well into the school year, I distinctly remember in gym getting up the nerve to ask the two worst bullies – who were always side-by-side – the question that had been on my mind ever since the year began.

“Why are you guys so mean to me?”

It didn’t take them even a moment for one of them to provide the answer.

“Because it’s fun.”

And there it was. The reason for all this bullshit had nothing to do with any particular “problem” on my part. They picked on me because they liked to pick on me. And that truthful answer didn’t give me any relief; it simply convinced me how cold these people were, and how vulnerable I was to any prick that decided he would give me a hard time. Because there was nothing I could stop doing to make the tormenting cease. There was no set of rules I could obey to get these people off my back. They did it just because they liked being mean. And I would be available to them every weekday, by the laws of the state, so they could have their fun.

I was the ideal target for a bully, because I didn’t fight back. Others might have hit them in the face, or – as is the case on a regular basis somewhere in America – put a bullet through their heads. I simply muddled through the 7th grade, miserable and wishing I was anywhere else.

In the spring of 1979, I was accepted into the charter class of the Baton Rouge Magnet School. This was going to be my salvation. I was going to join a school of smart kids. I was going to leave all these mean assholes behind. I could hardly wait! At last I was going to love learning again, and those future gas station attendants would continue to be imprisoned at Sherwood, far away from me.

Around the same time, though, my parents sat me down and told me that we would be moving to California. So while I had felt like “the new kid” entering the 7th grade, this time I really was going to be the new kid. I was disappointed that I wouldn’t be going to the Magnet school, but at least I was going somewhere different. Maybe the kids would be nicer in California.

They weren’t.

It seems that a small subset of geographically well-distributed boys around age 13 are genetically destined to be obnoxious, abusive pricks. We had them in Louisiana. And they certainly had them in California, as I would soon discover.

In the June of 1979, I flew out to California with my mother – – my father was already there – – and I stared down at the San Francisco Bay Area, my new home. Given California’s reputation, I was expecting some kind of Beach Boys paradise, but as I looked out the tiny airplane window, I saw the grotesquely-colored ponds that are along the perimeter of the Bay to this day. I know now that they are salt evaporation ponds, but to my young eyes, it looked like we were entering the land of toxic waste dumps. It was hideous.

Since I’ve always been very goal-oriented, one lingering item left unfinished from my Louisiana days was my Eagle Scout award. I was only 13 years old, but I was a Life scout, and I almost had my Eagle. My brothers had been Eagles, and I wanted to do the same, so one of the first things we did in my new home was meet with the Scoutmaster of the local troop and join.

I had been in a leadership role in my old troop, so in spite of my age, the Scoutmaster made me an staff member of the troop (about the lamest role there is – Quartermaster – but a staffer nonetheless). I was told we were going on a week-long hike to Bucks Lake in the Sierra Nevada mountains that summer. This would be my introduction to some of my peers.

As I mentioned earlier, there wasn’t anything out of the ordinary about me that should have prompted the taunts in Louisiana, but in my new home, there definitely was: I was from the South.

Thus, instead of calling me Tim, they called me “Beauregard”. They asked me if I was part of the KKK. They wondered if I ate fried chittlin’s (a term, I suppose, they had gleaned from old Beverly Hillbillies episodes). Little did they know that my neighborhood in Baton Rouge was almost indistinguishable from my new home in the East Bay of San Francisco. Except, as it turned out, for the names of the requisite assholes.

One of them in particular – Rob Tamaro – singled me out for punishment. He would call me all kinds of names, and near the end of our week hiking, as nervous as I was about the 8th grade, he assured me that at my new school: “they are going to rip you apart.” My stomach sank.

So I began the 8th grade at another new school – Joaquin Moraga Intermediate. It was largely a repeat of the 7th grade, although the different demographics at least yielded a larger quantity of relatively smart kids. But gym was still awful, and it didn’t take long for me to figure out who the bullies were, just as it didn’t take them long to figure out who was their new target.

The irony of Rob Tamaro is that he was actually really, really smart – a math prodigy, in fact. In retrospect, I believe he used bullying as his own shield, since he was afraid of how he would be caste if he were seen as a math whiz. The truly unfortunate thing is that we could have probably been good friends, but he decided to abuse me at almost every opportunity.

Attitudes toward gay people (that is, actual gay people, not the millions of “gay” 7th and 8th graders) have changed for the better in recent decades, but back in 1980, it must have still been pretty awful. There was an art teacher at school – Mr. Mast – who was quite obviously gay, and there were plenty of snide remarks he had to endure.

He was a teacher, so the remarks were fairly underhanded, of course, until the very last day of school. As the end-of-class bell rang, one of the kids, who had obviously been looking forward to this moment for a long time, yelled out “Bye, fag!” as he dashed out of the classroom. What an idiot, and what a coward. I can only imagine how Mr. Mast must have felt dealing with these little shitheads.

9th grade started, and – here we go again – this time the resident asshole was Bob Kully, who by misfortune had a surname alphabetically next to mine, meaning he’d always be next to me as we lined up by name for gym.

9th grade started, and – here we go again – this time the resident asshole was Bob Kully, who by misfortune had a surname alphabetically next to mine, meaning he’d always be next to me as we lined up by name for gym.

(I will also note, it occurs to me that the Roberts in my life, first Tamaro, and now Kully, seemed, in fact, to be Dicks.)

I pleaded with the school guidance counselor to change my schedule, which he did, but only after lengthy begging on my part. Next time I saw Kully in the school hallway, he slapped me – hard – in the chest, which is the closest I’ve ever come to being struck. I guess he was angry that his latest taunt-target had escaped. Without Kully assaulting me in gym each day, the year was somewhat more tolerable.

So for three years in a row – the 7th, 8th, and 9th grades – I was in a new school, each of those years was awful, and each of those years, academically, was largely wasted. 50% of my public school education was flushed down the toilet by a combination of inept teachers and brutal bullies. And I ask myself again – as I do on almost a weekly basis – how I might have turned out had it been different. What would I be like?

But that’s just backward-looking speculation.

As I wrapped up my 9th grade year, I wondered if the annual drag would persist indefinitely.

Then something changed.

Just as “something” terrible happened in the summer between grades 6 and 7, something magical happened between grades 9 and 10. Entering the 10th grade, the landscape was different. Shitheads weren’t the heroes anymore; it was the sharp, clever kids that were getting the attention. And I discovered that I could take classes that the shitheads didn’t want to attend. Smart people became a self-selecting group.

Miramonte High presented itself, in the 10th grade, as a place where I could finally belong. It was a place where I could feel safe. And – most important – it was a place where I could be myself. I was really into computers by then (having starting in with them three years prior), and I was getting paid to write for computer magazines. I had a pretty girlfriend. I had a contract to write my first book.

And that’s when the yellow jacket came out.

No, I’m not talking about the insect, and I’m not speaking metaphorically. I’m talking about a literal yellow jacket. It was a Izod Lacoste jacket – pale yellow – that was sort of like a windbreaker. It wasn’t loud or garish. It was actually pretty simple. But it was yellow. And I wore it. And I didn’t worry about being called names anymore. Because I finally had enough confidence to walk the hallways and, by way of my pastel-colored clothing – tell the world to go fuck itself if it didn’t like me or my faggoty jacket.

It might seem comic to read about it now, but reflecting back on those years, it struck me how important an act it was for me. I didn’t try to fit in anymore. I cut my hair nice and Republican-short. I wore preppy-looking clothes, and I wasn’t the least bit concerned about speaking up in class and getting good grades. And, by God, I was going to wear my favorite jacket, even at the risk of being called gay. Because, fuck you, I liked my jacket.

The balance of my high school days were the best years of my life. I was finally happy again. And, as candid as I am being with you, dear stranger, I’ll tell you I’ve never been that happy since.

In those days, I truly enjoyed all the things I could get out of life. I was at the sweet spot of adolescence when one can enjoy the benefits of adulthood (lots of money, a fast Porsche, a beautiful girlfriend – – who is now my wife) without any of the responsibilities (bills to pay, kids to drive from place to place, family pressures, and all the other heartaches of adult life).

And even though I was finally happy and free again, I realize now that the damage was done. The middle-school years made deep scars that are with me to this day.

“Get over it, Tim.” That’s very easy to say. As easy to say as any other little aphorisms you might have tossed to me as a 12-year old since, after all, words can’t really hurt a person, can they?

But here I am, well into middle age, and the taunts of mental midgets from a third-century ago haunt me on a daily basis, in ways big and small. Those voices have poisoned my psyche and created a very dark worldview and an intrusive pessimism about my own future. The same voices no doubt have a mutating effect on my trading.

But this blog – now in its 9th year, and frequented daily by people like yourself – has become a healing place for me, largely because I am able to create the kind of safe environment that I wish I could have crafted so many years ago for my young self. That is, a place where smart, interested people can share their ideas, their frustrations, their hopes, and their knowledge.

This perhaps also clarifies why I’m so obsessed with Slope being a friendly, welcoming place. When I see someone being nasty, it brings back too many bad memories, and I just don’t want them here. They belong somewhere else. This is a garden that good people can nurture, and from time to time, we get rid of the weeds.

We can all share a common notion of “the light” as being a disposition toward life and our world in positive, growth-oriented ways. My own distance from the light is something I struggle with on a daily basis, and the ugly experiences I went through as a young person have, I believe, created this struggle. I work some of it out through my writing, and the fact that so many people read it is helpful to me and, I hope, in turn, to some of you.

I had been thinking of doing this post for a long time, and I had already started outlining it when I happened to see a movie called Bully, which was released in 2011. Watching it was horrible, because I saw the same kind of thing I had experienced, but in worse form, by way of this documentary. Some of the kids profiled had killed themselves – – which I can certainly understand – – and others chose to fight the good fight. Seeing the meanness of those in junior high hadn’t changed in all these years made me sad.

The things we say to one another matter, and, above all, I will endeavor to protect my own children from the abuses I suffered, with the hope they won’t wind up as messed-up as I am today. If there’s any good that can come from I went through, it will be to at least give my own children what I never had: a great childhood with a superb education, start-to-finish.

Let’s treat each other kindly. And let’s help teach the others in our lives to do the same. The echoes from those voices decades ago still are with me, and I wish for you, and for myself, whatever healing needs to happen for us to let go of that pain. It hurt then, and it harms now.