The Dark Index (DIX) is a simple metric that tells us whether investors are using dark pools to buy or sell shares of S&P 500 component stocks. When it’s high, investors are buying. When it’s low, they’re selling.

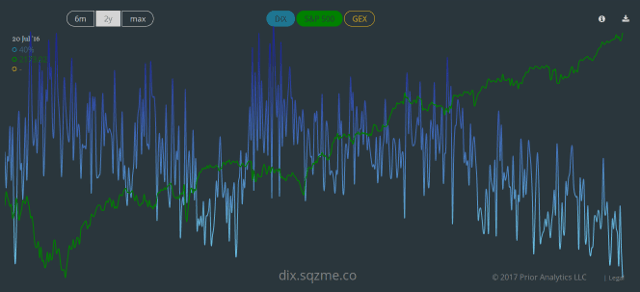

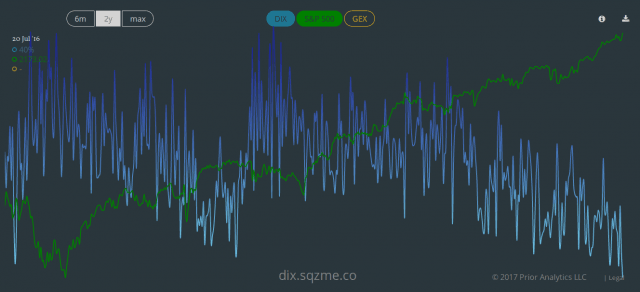

The blue line is the DIX. The green line is the S&P 500.

Key point: This is the lowest the DIX has been in two years.

Huh? Dark Index?

Somewhere around a third of stock volume happens away from public, or “lit,” stock exchanges. Investors send their orders to dark pools when they want anonymity, better fills, or lower cost. If you’re a large investor, chances are good that you try to route your orders through dark pools before you go to the lit exchange.

The Dark Index looks at every S&P 500 component’s dark pool volume every day and algorithmically determines whether those dark trades were likely buyers or likely sellers. When all of this data gets mashed together, the big picture of dark pool traders’ sentiment takes shape—and we like to think it’s pretty interesting.

Proof, Pudding

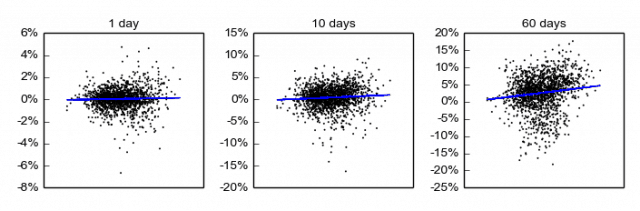

Historically, if you’d bought the S&P 500 when DIX was at the high end of its range (dark pool buyers), you’d have done really well. To illustrate that point, take a peek at these scatterplots. On each plot, higher DIX is to the right of the x axis.

On a 1-day timeframe, you don’t see much, right? But as time marches on (look at the 60-day plot), the linear regression line shows a clear slope. To boot, a rather clear clustering of nice returns shows up when DIX is high. In fact, the best returns only happen after the DIX has been high—when there are a lot of stock buyers in dark pools.

Why the lag, though?

It’s conventional wisdom that when someone buys a lot of stock, the price goes up. So why, if there are so many investors buying shares in dark pools, does it take so long to see the resulting returns? It’s actually not too hard to understand, but go grab a coffee if you have to.

Alright. Remember how big investors like to use dark pools for anonymity and all that? Well, another reason to use a dark pool is to reduce market impact. Most dark pools fill orders at the midpoint between the bid and the ask. Which means that a whole lot of shares can trade with a long or short bias without actually touching or moving the bid or the ask.

In effect, this means that an investor who buys a bunch of shares in dark pools (say, over the course of several weeks), doesn’t actually move the price. Instead, there’s more often a lag as the effect of the demand filters through the market.

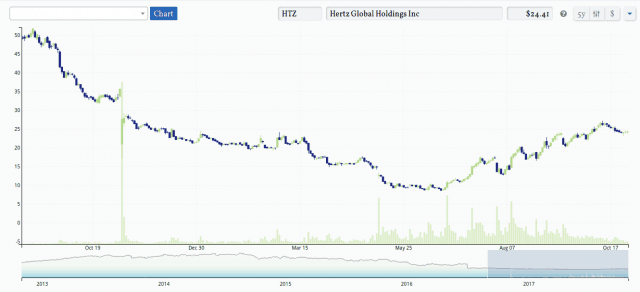

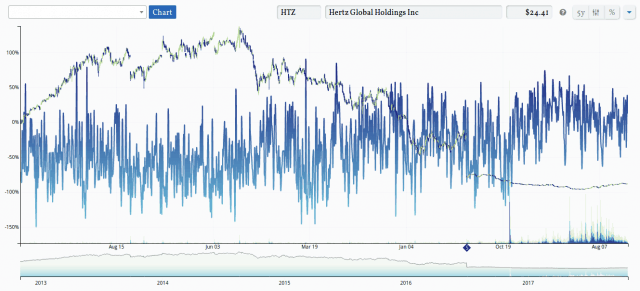

An extreme example of this is in Hertz (HTZ), which has had a 100%+ recovery in price since June. Nice, right?

But what you probably didn’t know is that dark pools were alight with eager buyers through nearly all of 2017. It just took time to work itself out. (The blue line below works exactly the same way it does for the DIX.)

Get the idea? OK, now there’s one more question to answer:

Will dark pool selling always foretell a downturn?

And the answer is: Often, but not always. The S&P 500 is a really robust index, and even if a lot of fundamental investors are selling their shares, the index can hang on for a long time.

But with that said, dark pool selling in S&P 500 components definitely increases the risk of correction. Hopefully we don’t have to explain why.

Now look at the 2-year chart of DIX again and tell us what you think.

Don’t know about you, but we’re ready for a correction.