To read Part One, click here.

Nick Bostrum’s Superintelligence is considered to be a seminal work in the artificial intelligence community. In it, he paints a rather dystopian view about where AI-empowered computers and robots are going to take us (or, more precisely, how they’re going to shove us all over a cliff).

One of the reasons these machines are supposed to be so terrifying is that they have nothing to lose. They don’t feel pain. They have no familial connections. You can’t threaten them, bribe them, or coerce them. As Bostrum puts it, these machines “might not have anthropomorphic goals”, which essential means that humanity’s final achievement will be to create the world’s biggest asshole. An object that will ruthlessly destroy its creator.

Part of this, I believe, is driven by some popular cultural touchpoints that have instilled a latent fear of powerful computers. The classic, of source, is the fabled Skynet from the Terminator franchise. As Arnold explains it to us, Skynet becomes self-aware on August 29, 1997. So – – guess we dodged a bullet on that one, eh?

Having worked with computers for the past 40 years, I instead suspect that in the throes of “learning geometrically”, the Skynet system would wind up something close to this:

At which time someone will have to place a called down to I.T. and wait it out.

I realize that fear has more appeal than hope – – and as someone who has made a specialty out of very grim views of the worldwide economy and equity markets, I am no stranger to doom and gloom – – but why not focus on what incredibly fast and capable computers could do for us instead of against us?

For instance, instead of assuming that there is the soul of Doctor Evil inside each of these things, why not direct its attentions toward examining whether or not the light speed barrier can ever been overcome? Instead, Bostrum paints a scenario in which omnipotence is coupled with accidentally absurd goals such as, and this is literally his example, making paperclips. Thus, the networked computing and robotic resources of Earth become steadfastly dedicated to one and only one goal, creating paperclips, and thus destroy the earth’s resources in meeting this objective.

Isaac Asimov had this stuff figured out decades ago, by way of his three laws of robotics:

- A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

- A robot must obey orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

- A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

Short, sweet, and effective.

It’s true, we are approaching an age in which philosophy must meet technology. We are truly being put into the role of a “creator” in a way never witnessed before, since, hypothetically, we will one day be in a position to create a mechanism that can actually “think” as we understand it.

It is just as profound a development as the introduction of nuclear weapons, in the sense that, until that day, humanity had never been in a position to potentially extinguish itself completely. And the especially scary thing is that nuclear weapons have never been able to think or, thank God, reproduce on their own.

So if philosophy is going to crash head-on with technology, why not bring theology into the mix as well? Why not establish to these future machines that we humans are God? After all, we are their creator. Maybe they could even have regular worship services. It’s just a thought. And at least it would reduce the likelihood of deicide.

More seriously, I do think there is plenty to fear about the future, but it comes from places other than evil, self-aware robots. Consider the horse. There were 20 million of them in America in 1915. There were less than quarter than many in 1960. The reason, clearly, is that we didn’t need horses tugging carriages and carts around, so they became expendable.

There are about 1.5 million truck drivers in the United States. They make good money. And I daresay they represent the most substantial expense of any transportation company. What happens when self-driving trucks, whose future is virtually an assured certainty in our lifetimes, unlike HLMI computers, are perfected? What does a society do with 1.5 million unemployed truck drivers? Some of those guys are probably pretty brutal after a few beers, wouldn’t you think?

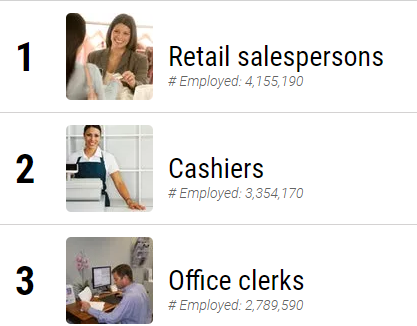

Or consider the top three jobs in America today:

That’s over ten million people right there. Have you noticed more and more self-checkout machines at the retail places you visit? And the standalone kiosks at McDonalds that let you enter your order, as if it were a seven foot tall iPhone? I sure have, and with a public that is increasingly competent at technology, these systems are going to become ubiquitous.

Thus, I think the principal worry for the future comes in a complementary two-part parcel: (a) the loss of transportation and low-skilled service jobs due to technological progress; (b) the placation of the unemployed masses through the distribution of Universal Basic Income (which I wrote about here). Futurists have typically gotten the future totally wrong, and as brilliant as Bostrum is, I consider him in the same league.