I’ve been pleasantly surprised that some of my most popular posts are excerpts from the only history book I ever wrote, Panic, Prosperity, and Progress. Over this holiday weekend, I’ll be sharing, over the course of four days, the chapter dedicated to the inflation and bursting of the Japanese bubble of the 1980s. I think you’ll find some interesting parallels with China. You can read the first part here.

In the early 1950s, Japan focused on what it called “priority production”, which meant a focus on basics such as coal mining, steel production, and shipbuilding. It was creating a solid foundation for the widespread industrialization that would come years later, and it helped move the country away from its former focus on farming. In the modern world, becoming proficient at industries such as steel would be more valuable than another marginal increase in rice output.

The Japanese recognized they had a special talent for monozukuri (“thing-making”), and throughout the country, one- and two-man businesses set up shops in spare bedrooms, garages, and extra offices to manufacture whatever they think they could sell.

At first, “Made in Japan” was synonymous with cheap, shoddy, copycat products. Japan did not yet have the experience or infrastructure to create high-quality products, but what the rest of the world did not realize is that, in steps, Japan was working its way up to becoming a formidable competitor. Although Japan’s resources were limited, the ability of its citizens to learn from and, more importantly, improve upon the ideas, products, and techniques of other countries would become its greatest asset.

Even though the years after war’s end had saved Japan from starvation, it was still a very poor country, and almost all its citizens struggled just to get by. In 1950, an average Japanese citizen had the same income as a person living in Ethiopia or Somalia. It was fortunate for Japan that a war was taking place (specifically, the Korean War) that was close enough to be economically helpful but not so close as to be dangerous, but once the war ended, it was unclear how Japan could thrive on the world scene on nothing but cheap knock-offs from the great economic powers.

This reality was summed up succinctly by none other than the U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, who said of the Japanese that they “…should not expect to find a big U.S. market, because the Japanese don’t make things we want.” It may have been true at the moment, but that statement would soon face a very different reality.

The Soaring Sixties

The Korean war gave the resources and the reason to build up a more substantial industrial infrastructure, compelling the nation to invest on factories and equipment. In what would become a theme for decades to come, the Japanese would visit and learn from factories in other more-developed parts of the world and bring those techniques back to Japan. Subsequent improvements would, in time, make Japan a more efficient and cost-effective producer of whoever they copied in the first place.

By the early 1960s, Japan’s recovery and reputation had made such progress that it was honored to be the host of the 1964 Olympic Games in Tokyo. In fewer than twenty years, the country had gone from a devastated wasteland to a relatively prosperous and recognized global participant. The Olympic Organizing Committee made this official with their selection.

The economic growth of Japan in the 1960s was astonishing. Whereas most industrialized nations considered a growth rate of perhaps 2.5% or 3% per year to be healthy, Japan was experiencing annual economic growth that reached into the double-digits. The growth rate by the late 1960s was nearly 11% annually and, in an event that no one would have dared predicted just a decade before, Japan was the second-largest economy in the world by 1968. Only the United States, its former opponent that restored Japan to economic health, was larger.

In spite of the divorce between government and business that the U.S. had demanded at war’s end, the Japanese government had re-established a variety of healthy and largely beneficial ties between its national government and the companies within its borders. Perhaps the most important of these was the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI), which acted as a brain trust, finance arm, and advisor for the important industries of the country.

At the same time, in spite of the elimination of zaibatsu, a somewhat new form called keiretsu was conjured up, which promoted integration among related companies. Companies in strategic industries (namely power, coal production, steel production, and shipbuilding) were supported and guided by MITI, and cross-ownership among key companies in these fields was actively encouraged.

The keiretsu were also encouraged to eschew the short-term focus of their Western competitors and focus on long-term economic growth and profits. The “long-view” became the desired perspective as far as the MITI was concerned, and – – as with lifetime employment and widespread employee unionization – – a focus on long-term profits instead of short-term results became a relatively unique aspect of the Japanese economy on the world scene.

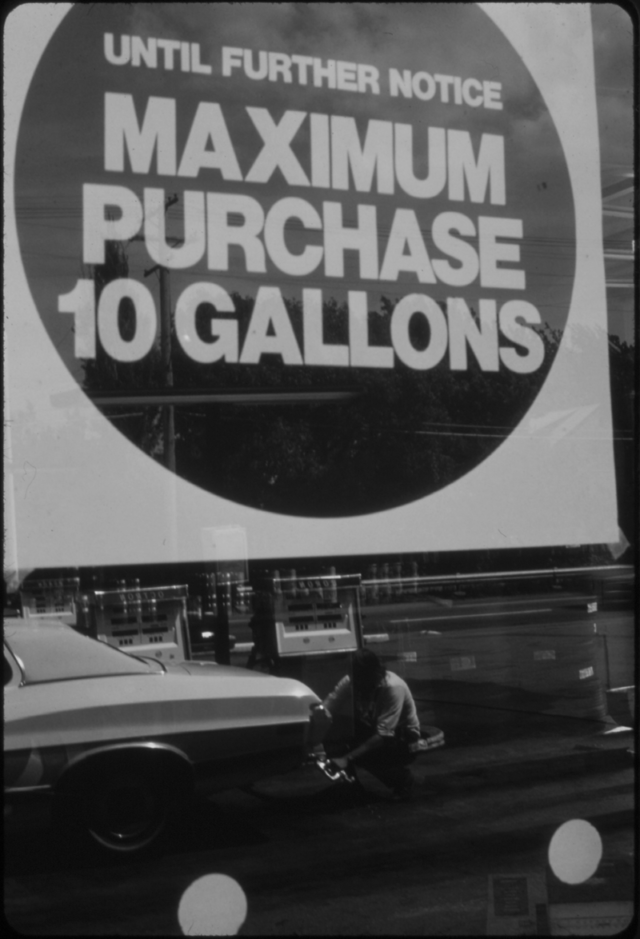

OPEC and Little Japanese Cars

Just as the Korean War had provided unexpected benefits to Japan in the early 1950s, two decades later, a different problem would again been a boon to Japan: the energy crisis. When OPEC exercised its muscle during the early 1970s, the price of crude oil (and, in turn, gasoline) shot higher. Detroit, which since the inception of the automobile had been the world leader in car production, was still producing millions of over-sized, overweight, gas-guzzling cars that were instantly less attractive to the buying public.

There was an alternative, of course, in the form of Japanese cars. The small, low-cost, gas-efficient cars from Japan had never become very popular the U.S., but the gas crisis gave them a new reason to be attractive. Datsun (the name of the company today known as Nissan), Honda, and other Japanese car makers latched upon the opportunity to sell their fuel-efficient vehicles to overseas markets that were confronted with much higher gas prices.

As Americans began to embrace Japanese autos, they discovered other advantages. For one thing, Japanese manufacturers were very progressive in their use of robot technology in their plants. Robots don’t go on strike and, by definition, they don’t make human errors. Thus the cars tended to be of higher quality than similar U.S. offerings. In addition, because of Japanese manufacturing efficiencies, makes such as Honda were far more economically-priced than Ford or General Motors products.

The rising success of Japan was juxtaposed by the decline of the United States. Once-proud industries such as steel and autos began to decline with alarming speed in the U.S., and terms like “the rust belt” were used to describe sections of the U.S. that had formerly been areas of widespread middle-class employment. Resentment started to grow that the Japanese were somehow being “unfair” by offering attractively-priced products that were more efficient and popular than the American equivalents.

Electronics Giant

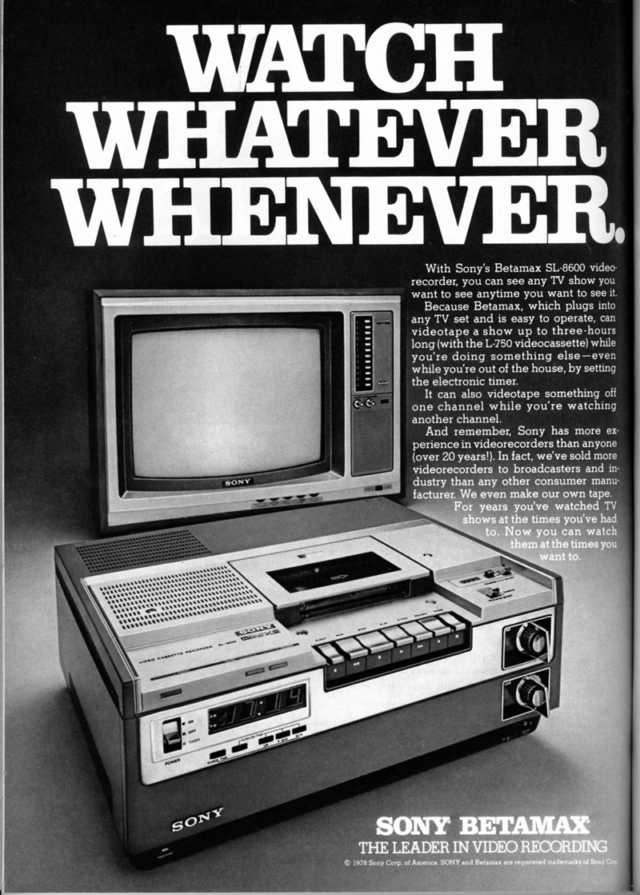

Alongside Japan’s success with cars was its growing dominance in electronics. Sony had offered its first transistor radio to the market back in 1955, but by the late 1970s, the most respected and innovative makers of consumer electronics were the Japanese. When Sony introduced its Walkman, for example, it became an international sensation, much like the Apple iPod that would be introduced a quarter-century later.

Japan started to get a reputation as a kind of modern-day utopia, with content workers, an unstoppable manufacturing marvel, and the world’s longest life-expectancy. It became easy to speculate that the United States and the Japan would eventually switch roles: that is, with the U.S. on the decline, with its overpaid workforce, inferior products, and shrinking industries, it would soon found itself in the #2 economic spot that Japan had occupied for so long.

The late 1970s and early 1980s experienced a tremendous growth in the variety and popularity of consumer electronics. Old standbys like televisions, speakers, and radios were still popular, but new products were introduced such as the Betamax and VHS video recorders, video cameras, and personal computers.

Japan made important inroads in virtually all aspects of electronics, particularly semiconductors, computer components, and printed circuits boards. Just about the only two areas that Japan hadn’t achieved domination were integrated circuits (dominated by the U.S. firm Intel) and software. It was widely believed that it would not be long before Japan captured those areas as well, since it had proven so adept everywhere else.

American firms became envious of the remarkable prosperity in Japan, and organization in the United States tried to mimic the behavior of their overseas competitors in ways that, in retrospect, seem somewhat comic. Many blue-collar workers in Japan would begin their workday with calisthenics, for example, so some American firms, in a stellar example of confusing correlation with causation, told their workers to start performing calisthenics as well. Not surprisingly, this did not create any kind of miraculous turnaround.

Meanwhile, Japan’s coffers continued to grow. Japan was the number one creditor nation on the planet, and it was consistently the largest exporter. The Japanese economic miracle was studied, discussed, and imitated, and although the end of the 20th century was still years away, academics discussed the very real possibility that the “American Century” (the 20th) would yield to the “Japanese Century” (the 21st), just as America had closed the door on the “British Century” of the 1900s. It was an alluring and easy-to-believe narrative. As we know today, it was also dead wrong.