Compulsion to Repeat

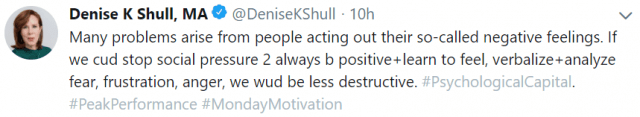

Sigmund Freud was the first to recognize that some people behave not out of a desire to seek pleasure, but out of a “compulsion to repeat.” This theory details how some people endlessly repeat patterns of behavior that are associated with difficult or traumatic events in their lives, particularly early life. In this article we will take a modern day look at Freud’s repetition compulsion. Denise Shull, in the below paper, details how today’s neuroscience intersect with Freud’s “compulsion to repeat”. Let’s take a look.

The Neurobiology of Freud’s Repetition Compulsion

Shull begins with a basic analysis of neurotransmitters, and how they operate within the brain. She discusses serotonin, dopamine, and adrenaline. These neurotransmitters are shown to play a key role in learning, memory, and emotion. “They can arrive rapidly – within 50 nanoseconds – in response to an emotionally sensitive event.”

She then discusses different parts of the brain involved with emotion and behavior. You can see the same parts of the brain discussed that Dimasio also discussed. Shull focuses on the amygdala being critical to the formation of compulsion to repeat patterns.

“Extensively connected with both lower brainstem and higher cortical brain centers, the amygdalae perform somewhat like Grand Central station. Rolls noted that these connections imply that the amygdala receives highly processed sensory information and in turn influences autonomic, motor, and some cortical processing (1992). Research in the last ten years repeatedly indicates that the amygdala is central to unconscious processing, emotions and social behaviors. Schore indicates that parts of the amygdala experience a critical period of growth during the last trimester before birth and in the first two months of life (2001a). This suggests a pivotal position in the creation of both a repetition and the compulsion associated with it.”

Denise Shull

Shull then discusses neural networks, how different parts of your brain work together as a circuit to complete or process a task. Once such network involved in emotion is termed the limbic system.

She then goes on to detail how the human brain develops. The amygdala is active at birth. The cingulate becomes active within 3-9 months, and the orbitofrontal cortex within 10-12 months. This timeline of growth gives evidence to how emotions felt in the first few months of life can become unconscious. “It also explains how early experiences maintain such power: each lower structure of the brain modifies development of the next higher one”

Ultimately, “The orbital cortex matures in the middle of the second year, a time when the average child has a productive vocabulary of less than 70 words. The core of the self is thus nonverbal and unconscious, and it lies in patterns of affect regulation”

Denise Shull

Shull continues with a discussion of how the level of neurotransmitter usage during these first few months of life can remain in place. She gives an example of adrenaline. If a child is exposed to a threat, enormous tension, or trauma repeated surges of adrenaline can be excreted. In this case the receptors of the neurotransmitters may alter their receptivity to adrenaline in order to maintain a baseline amount. She gives an example of how few receptors for adrenaline have been found in patients with borderline personality disorder. This has the effect of the body continually producing and releasing excessive amounts of adrenaline in these individuals. Shull contends that this process can setup a reactivity to neurotransmitters in individuals that have had these experiences. “Later in life, the adult may thus be sensitive to situations reminiscent of the early experience. According to the repetition compulsion, he will even set out inadvertently to create a similar situation.”

Long term potentiation is also discussed. This involves how when a neuron receives a series of rapid stimuli over a brief period of time, future reactions of this neuron are increased with only a single stimuli. “In other words, once the neuron gets pounded, it only takes a light tap to produce subsequent firing.” An important point here is that the neuron don’t forget. This process endures, and year’s later even a light tap to that neuron can yield the same result. This is another foundation to the concept of repetition compulsion.

Next, the subject of memory is discussed. “Malignant memories” is a term that was coined by Perry & Pate, who were working with individuals with extreme PTSD. Denise shows how these memories are stored as implicit memories, unconscious through the amygdala.

“They described how malignant memories become the preferred approach for integrating information based on a prolonged reaction to a past threat. In the case of a sudden traumatic event, the brain’s reaction mechanisms fire so intensely that an overpowering memory is created. The scenario of PTSD resembles the theoretical substance of a repetition in that something repeatedly stressful, albeit unknown, creates an ongoing reaction to a historical event. We can see how the repetition compulsion essentially embodies the existence of a malignant memory.”

Denise Shull

Shull next goes on to detail the work of neurotransmitters further, including how oxytocin and dopamine can work together. She concludes, “Hence, it could be that the only path the brain knows to generate what may have been fleeting good feelings is to recreate the original circumstances, and this may drive compulsive behavior.”