It’s a quiet Sunday morning, and since there’s really nothing going on, I’d like to share with you a fun read in the form of an excerpt from the one history book I ever wrote, Panic, Prosperity, and Progress. It just goes to show that “fake news” is not an invention of the modern age, particularly when it comes to the financial markets:

Just as the value of the Greyback behaved as a proxy for the South’s war prospects, the value of gold reflected the military success (or setbacks) for the Union. Although financial markets were quite primitive at the time, necessity being the mother of invention led to the creation of “gold rooms” where spirited bidding would take place. A contemporary wrote of one such room, evoking the intensity of the scene that isn’t far removed from a modern-day account of a commodity exchange:

“The gloom or the gladness over success or defeat of the national flag mingled with individual passions. Men leaped upon chairs, waved their hands, or clenched their fists; shrieked, shouted; the bulls whistled ‘Dixie,’ and the bears sung ‘John Brown’; the crowd swayed feverishly from door to door, and, as the fury mounted to white heat, and the tide of gold fluctuated up and down in rapid sequence, brokers seemed animated with the impulses of demons, hand-to-hand combats took place, and bystanders, peering through the smoke and dust, could liken the wild turmoil only to the revels of maniacs.”

The importance of gold to the Union’s assets, and its value as a measurement of popular sentiment about the war’s prospects, were not lost on President Lincoln. He followed gold’s movement with a combination of interest and resentment that any man would try to profit from the horror of the war happening around them.

One dinnertime anecdote holds that Lincoln asked, “What is the price of gold this morning? Is it going up or down?” The aide replied, “Up, Mr. Lincoln. The Street is wild.” The President responded, “Well, now, they don’t know everything. If I were a bear on Wall Street, and if I were short of gold, I’d keep short. It’s a good time to sell.” It seems incredible to imagine a near-deity like Abraham Lincoln speaking in the language of a financial speculator, but such was the account.

The gold rush that commenced in California over a decade earlier turned out to be a godsend for the United States, which relied heavily on whatever stores of gold it could attain. General Ulysses Grant himself remarked, “I do not know what we would do in this great national emergency were it not for the gold sent from California.”

The opportunities to profit from gold’s dynamic price movements were not missed by the unscrupulous, and one fascinating account from 1864 captures this neatly. In May of that year, after four years of war, the Union was growing hopeful that a successful conclusion might be in sight.

However, on May 18th, two morning papers came out – the New York World and the Journal of Commerce – with shocking news: they stated that the President had ordered an additional 400,000 men to be conscripted into the Union army on account of “the situation in Virginia, the disaster at Red River, the delay at Charleston, and the general state of the country.”

The discouraging report and the demand for such a huge quantity of fresh soldiers sent a shockwave through the financial community, since it was obvious from the report that things were not going nearly so well in the war as once believed. Stocks tumbled, and hard assets such as gold soared in value. Some people became puzzled, however, because this important report was nowhere to be found in any of the city’s many other newspapers.

Late that morning, crowds had gathered at the offices of both papers that had published the news, and the editors assured them that the story was true, producing the dispatch from the Associated Press with the matching information. The Associated Press, however, the ostensible source of the information, quickly issued a statement making clear that they had never sent out this dispatch. This was soon followed by the State Department in Washington, in which the Secretary of State, William Seward, declared the news dispatch to be “an absolute forgery.”

It turns out that the forgery was a clever creation of Joseph Howard, the city editor of the Brooklyn Eagle newspaper. Howard, who was intimately acquainted with the workings of the city’s newspapers, had come up with a scheme. He knew that bad news from the war would cause gold to rise in value. He also knew that the best way to get a dispatch into the morning papers would be to submit the dispatch when the newspaper staff was most vulnerable – – that is, in the wee hours of the morning, when there were hardly any personnel around to verify the facts.

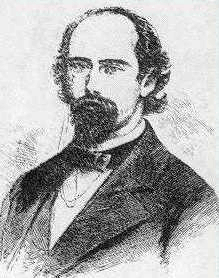

Joseph Howard, the mastermind behind the 1864 gold hoax.

Thus, working with an accomplice, he crafted a realistic-looking Associated Press news release and, working with one Francis Mallison (a reporter for his journal), he distributed the news item at 3:30 in the morning to the city’s newspapers. Most of them were reluctant to print such an important piece without verification, but two of them proceeded to run with the story.

Of course, before any of this took place, Mr. Howard had acquired as much gold as he could in his margin account, and once the grim news was raging throughout the financial community, he disposed of his position at a handsome profit, never suspecting the false item would be traced back to him.

It was, however, and President Lincoln himself ordered the closure of both of the papers that had printed the dispatch, which was an order later rescinded. Lincoln’s furious demand for the paper’s closures, however, became one of the few black marks on his presidency since, in spite of the ugly circumstances involved, went right to the heart of freedom of the press enshrined in the Constitution.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, this was not the first instance Mr. Howard decided to try to fool the public. Years earlier, in 1861, he wrote a story claiming that President Lincoln had traveled throughout Baltimore disguised – of all things – with “a Scotch cap and long military cloak”. Although Howard was thrown into Fort Lafayette for his crime, he was released a few months later.

The irony to the entire hoax was that only two months later, Lincoln did indeed order up the conscription of more men into the Union army. However, the figure demanded was not the 400,000 that Howard had dreamed up for his bogus news release. It was, in fact, a full half million. Howard’s fanciful fraud was, in the end, prescient.