With the focus on precious metals lately, I wanted to share a free chapter from my Panic Prosperity and Progress book about a germane period in financial history related to the California Gold Rush of the mid-19th century. Enjoy!

The California Gold Rush is one of the most universally-known eras of American history, but it is also one of the most widely-misunderstood. It obviously altered the importance of California (which today reigns as one of the most important technological and business powerhouses on Earth), but it was just as important to the history of the entire nation in the decades that followed gold’s initial discovery at Sutter’s Mill.

There were not any meaningful financial markets for it to affect, but the gold rush laid the foundation for some important personal fortunes and fundamental Californian characteristics that lived far past the middle of the 19th century.

An Empty State

It seems hard to believe that a state that presently serves as the home to over 38 million people was, not that long ago, almost entirely uninhabited. In 1848, California was still a Mexican territory, and of the 34,000 or so people in the entire state, 12,000 were Mexicans, 20,000 were Native Americans, and a couple thousand were white soldiers and settlers.

One of these settlers was a young man named Sam Brannan who had started a newspaper called The California Star in the tiny settlement of San Francisco. Brannan later had set up a store near a lumber mill owned by John Sutter, another newly-established businessman in the area. Brannan had traveled out West with his fellow Mormons and at one point urged the church’s leadership to establish its home in California (as opposed to Utah). Brannan was a hard-working, enterprising entrepreneur who enjoyed early success with both his newspaper and his store.

John Sutter, having befriended the Indians in the area, had established a large ranch of nearly 50,000 acres (which he called – of all things – New Switzerland) and, with the help of the Indians, had constructed a fort. He had great ambitions to become an agricultural powerhouse in the region, and he was building out the infrastructure of his holdings, including a lumber mill. So Brannan and Sutter, two businessmen in a state almost completely devoid of any inhabitants, nursed their business ambitions side by side.

On January 24, 1848, James Marshall, a trusted foreman working at Sutter’s lumber mill, found several chunks of a bright, shiny, heavy metal in the water from the American River. Both Sutter and Marshall were intrigued and, referring to an encyclopedia on hand, learned how to perform some basic tests to determine whether it was gold or not. They confirmed that it was.

One might expect Sutter to be thrilled that precious metal was on his property, but he knew that if word got out, his land would be overrun with strangers. He therefore sought to keep the discovery a secret. He asked Marshall to keep his mouth shut.

After a few of Sutter’s employees paid for their goods at Brannan’s store with gold, though, it became much harder to keep the secret. Although Sutter didn’t want word of the gold to leak, Brannan instantly realized that a flood of people in the vicinity of his store – the only store in the area – would be outstanding for his business, so he took it upon himself to return to San Francisco, vial of gold in hand, and shout out “Gold! Gold from the American River!” as he walked up and down the streets of the settlement. Naturally, word of the discovery spread like wildfire.

Brannan would have also have liked to have printed a story in his newspaper about the discovery to dispatch the news further, but his staff had already rushed off, like most of San Francisco (which at the time was called Yerba Buena) to snatch up the promised gold from the American River. By amazing coincidence, right at this time Mexico signed over the California territory to the United States as a consequence of the Mexican-American War. Everything was in place for an astonishing transformation in the region.

A Challenging Trek

The earlier people to get word of the gold were those relatively close to California, such as Mexicans. By August of 1848, word had finally reached the East Coast of the United States, and greatly-exaggerated tales of the easy riches to be had in California swept the land.

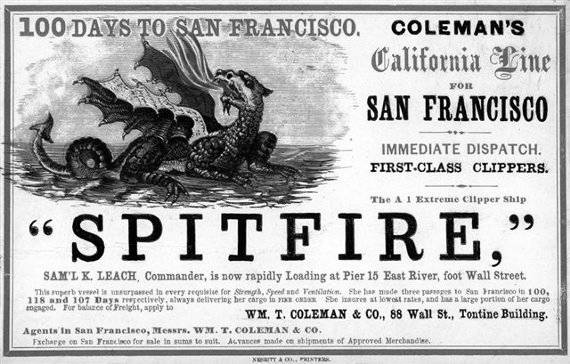

There were, at the time, three ways to get from the Eastern United States to California: (1) take a ship all the way around the coast of South America, and back up again, which took at least four months, and often much longer; (2) take a ship to Panama, then risk a malaria-infested journey to the other side of the isthmus to get on board another ship to complete the journey northward; (3) go overland, which had its own human-based peril. None of the three methods was safe or quick.

Even in faraway China, word spread about the Gum San, or Gold Mountain, that had been found, and enterprising agents distributed fliers in Canton and Hong Kong offering passage to California. Thousands of Chinese boarded ships to cross the Pacific Ocean, and within a few years, 20,000 Chinese would be in California (which constituted effectively the entire population of Chinese in the whole of the United States).

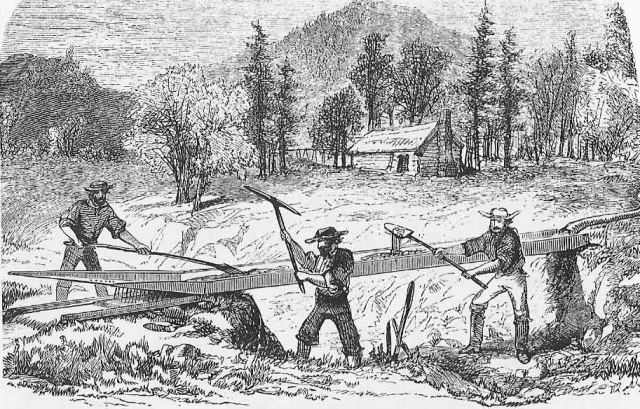

In the earliest days of the gold rush, there was a kind of excited camaraderie in the camps, since the feeling was that there was a vast treasure simply awaiting extraction for all brave enough to make the journey. A contemporary account held that “…the conviction was widespread that the mountains were a bank on which every man had a drawing account; if he came up short he need only seize his pick and pan and make a withdrawal.” The earliest miners were able to pan gold right out of the river with relatively little effort, and some of those who arrived in 1848 acquired staggering personal fortunes simply by the good luck of being there first.

This was no panacea, however. California was truly “the wild west”; there was no infrastructure, no enforced laws, no judges, no police, no plumbing, and very little in the way of food or comfort. The territory had just passed into American hands, and whatever justice might be dispensed was often handled by “Judge Lynch” (that is, not an actual person, but instead a rope and an angry mob). Disease and discomfort were a constant, and an alarming 30% of the original settlers died from sickness, violence, or accident during the gold rush years.

The dangers were worth the profits, however, since a man armed with nothing but a pan could earn ten to fifteen times as much in a day as he could earn doing regular work. Making a lot of money suddenly didn’t require education, a license, talent, or strength; it only took the will to show up and step into the river with a pan. Whatever you find was yours, free for the taking, and not even subject to taxation. It is not surprise, then, that the easy gold was found and removed within a year’s time.

Disappointed Latecomers

Those from the East Coast who had traveled the 18,000 miles around the tip of South America expecting to find their fortune were soon disappointed. During the years of the gold rush, hundreds of thousands of people, all with the same dream, showed up, and while they made people like Sam Brannan rich, they usually found themselves completely devoid of the metal they came to acquire.

Brannan himself took a small place in California history by becoming the state’s first millionaire, and he rapidly acquired land in San Francisco, Hawaii, and Southern California. (Incredibly, even though such land parcels were ultimately worth billions of dollars, Brannan died so broke that his estate couldn’t even pay for his own funeral).

Not surprisingly, the U.S. swiftly granted California statehood, skipping the traditional need to be a territory first, once its riches were known. As more and more people crowded into California to stake their claim, resentment and racism began to creep in. American miners looked down on the Mexicans, Native Americans, and especially the Chinese who had come to seek their fortune. The California State legislature cooperated in this racism, passing the Foreign Miners License Law, which required $20 per month (an exorbitant amount at the time) from anyone who was not a U.S. citizen.

One of the lasting legacies of this era was the influx of Chinese immigrants. Before the gold rush, the entire United States had essentially no Chinese at all. In 1852 alone, a full 20,000 Chinese came to California, and the large Chinese population on the West Coast of the U.S. to ay is a testament to the influx of Chinese who pursued the mountain of gold they had been told about.

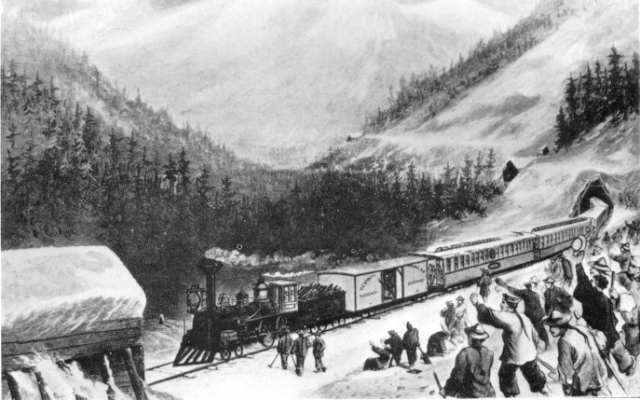

As the Chinese were chased away from gold-mining, both through threats of physical violence as well as punitive legislation, they eventually found work in industries such as railway construction. Indeed, during the 1860s, the Chinese proved themselves to be reliable, brave, and hardworking, with over 10,000 Chinese employed by Central Pacific at one point. By 1870, there were nearly 70,000 Chinese in the U.S., almost every single one of them living in California.

A Distorted Economy

The economic law of supply and demand became very apparent during the gold rush, since there was a surging demand (the explosive influx of humanity) and a relatively constant supply of goods. After all, only limited amounts of merchandise and foodstuffs could be had in a state that was almost entirely unpopulated before the gold rush commenced.

Some of the prices charged for everyday goods, adjusted for inflation, make clear how prohibitive living in the gold rush days must have been:

Beef – $280 per pound

Butter – $570 per pound

Cheese – $700 per pound

Eggs – $84 each

Rice – $230 per pound

Shovel – $1,000 each

Some stores would also offer services at very high prices, since time was precious to the miners. The miners were eager to hear from home, and their families would spend 40 cents to send a letter from the East to California. The store owner, in turn, would charge three times that much just to head into town where the post office was located and bring them back their letter. The store owners were just as happy to demand the same fee to take the miner’s reply and bring it back down to the post office.

Services were so scarce that it was actually cheaper to ship laundry to Hawaii (then called the Sandwich Islands) for cleaning instead of having it laundered locally. Thus, shiploads of filthy shirts, pants, and undergarments sailed thousands of miles across the Pacific for washing. And San Francisco real estate – in a tradition that persists to this day – would yield handsome profits for those lucky enough to get in early. A parcel that might have sold for $16 before the gold rush would now yield one-thousand times that amount. It is not surprising that Henry David Thoreau, taking in the spectacle from the other side of the country, quipped “Going to California…is only three thousand miles nearer to Hell.”

Another sign of how perverse the mindset of the time became was in the form of the ill-named Act for the Government and Protection of Indians, passed in April 1850 by California’s new legislature. The law actually did nothing to “protect” the Native Americans; on the contrary, it expressly allowed for the white settlers to capture and enslave the Indians as workers.

In spite of California piously disavowing the Southern practice of slavery, it permitted the buying and selling of Indians, particularly young women and children. During the gold rush years, about 4,500 Native Americans died at the hands of whites, and the overall population of Native Americans dropped from about 150,000 in 1845 to fewer than 30,000 in 1870.

On the Farm

During the gold rush years, the majority of people in California were miners. Even as early as 1850, about two-thirds of the state’s entire population was engaged in gold mining, and since most workers left their regular jobs, those who were willing to remain in more pedestrian forms of employment saw their wages soar six-fold, since there was simply no one else around willing to do the work.

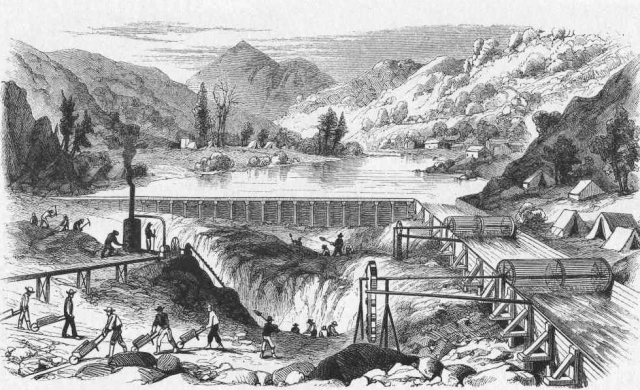

Those who were working the foothills of California for gold added greatly to the nation’s available gold supply. As the easy-to-find gold disappeared, well-capitalized companies with large (and environmentally-destructive) drilling tools took over and amplified the gold extracted from the land. In 1848, not even a quarter-million dollars of gold was produced in California. By 1852, nearly $82 million was produced. (This year would be the peak of the gold production of the time, with subsequent years yielding substantial, but still slowly dwindling, figures).

Some additional perspective can be had from this fact: in 1849, well before gold production had reached its zenith, there was more gold extracted from California alone than had been extracted in the entire United States in the preceding sixty years. The United States monetary system was based on gold, so the insertion of so much new metal into the economy also yielded inflation (somewhat like if an equivalent amount of paper money had been printed), so wholesale prices increased about 30% between 1850 and 1855 across the U.S.

California could not have found a more effective way to grow its population: the gold rush years pushed the population from its original 14,000 to nearly twenty times that amount, and although the vast majority of would-be miners abandoned their pans and pickaxes, some of them stayed in the state to find other gainful employment. Often this would be in agriculture, as there was a growing demand for food, and California had ample arable land.

The commercial endeavor that would spring forth from California that would have a far longer-lasting impact on the nation was the railroad business. Four businessmen who had prospered, much as Sam Brannan had, with sales to the new California settlers formed an alliance to create and manage the Central Pacific railroad.

These “big four” – Mark Hopkins, Collis Huntington, Charles Crocker, and Leland Stanford (for whose son the famed university would later be named) were in the proverbial right place at the right time. An intercontinental railway had long been the dream of the United States, but bickering between the North and South as to its pathway prevented the plan from ever going forward.

Once the Civil War was underway, and the South no longer had a voice in the United States government, the railroad was immediately approved (with, naturally, a relatively northerly placement of the tracks). The Pacific Railroad Act granted a $16,000 payment per mile for flat terrain, $32,000 for foothills, and $48,000 for the far-more-difficult mountain construction. Although it took most of the decade to complete, when the eastern-bound and western-bound construction finally met in Utah in May of 1869, the nation was finally linked coast-to-coast.

What this meant for California, of course, was it suddenly had access to a worldwide (rather than statewide) market for its food. With access to the entire East coast – and its ports for countries across the Atlantic, the points of destination for California agribusiness became global. By the late 19th century, while gold had been largely a thing of the past, agriculture had become California’s most abundant and profitable business.

Thus, the exciting, get-rich-quick part of the gold rush lasted not even a year, as those early and eager enough were able to pluck their riches straight off the ground or from the streams of the Sierra foothills. The real impact, however, of the mass migration into the state was a vital intercontinental link, an amplified national money supply, and a large, ethnically diverse worker base in the new state of California that would have a profound and permanent effect on the character of the state and the nation.