During these three-day weekends, I’ll sometimes lean on my Panic Prosperity and Progress book for an interesting morsel of content for my readers. Part 1 is here and Part 2 is here. Enjoy:

As the call rate lurched from 60% to 70% and, later, 100%, the metaphorical air supply of cash that normally enlivened the stock market was choked off. Equity prices started to sink badly, and by the afternoon of Thursday, October 24, Ransom Thomas, the president of the NYSE, went to Morgan’s office to advise him that they were going to close the stock exchange early. Morgan correctly asserted that such an act would only add to the panic and tumult, and he implored Thomas to give him time to help.

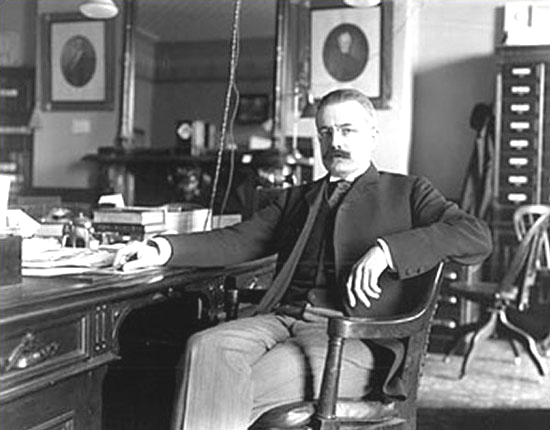

Morgan told the presidents of the city’s banks to come to his office at once, which they did within minutes. Morgan informed them bluntly that unless they gathered $25 million among themselves to provide the exchange, fifty brokerage houses would fail that very day. Within minutes, the presidents pledged nearly the full amount to the exchange, and the money reached the market half an hour before the closing bell. Morgan also tried to shore up confidence by making a rare statement to the press: “If people will keep their money in the banks, everything will be all right.”

The next day on the New York Stock Exchange was just as bad, and Morgan again had to lean on bank presidents to loan the exchange money – this time, in the amount of nearly $10 million, and the bankers were beginning to worry they were throwing good money after bad. Morgan knew he could not sustain this kind of cash infusion indefinitely, and that Friday he organized his team to form two committees, both bent on public relations: one of them was specifically for the nation’s clergy, to calm their congregations on Sunday, and the other was for the newspapers, to help explain the financial backing Morgan and his men were providing and why it would stabilize the situation.

The weekend proved to be just as restless and anxious as those that preceded it for J.P. Morgan. On Sunday, George Perkins – an associate of Morgan’s – was told by the City of New York that if it did not receive $20 million in emergency funding within the week, it would also go bankrupt. The mayor himself, George McClellan, appealed to Morgan directly on both of the following two days, and Morgan quietly agreed to purchase $30 million in city bonds. He did not publicize this additional financial backing, since he felt revealing the precarious situation of the city itself would only exacerbate an already very bad situation.

Roosevelt’s Reluctant Aid

During all of this, the President of the United States was enjoying himself in the wilds of Louisiana, hunting bear. He finished up his adventure and was slowly making his way back to Washington, D.C. On the way, he took time to give a speech lambasting the men of Wall Street and praising his administration’s tough stance against financial manipulation and railroad conglomerates. These sentiments, of course, did nothing to shore up confidence back in New York.

Roosevelt and Morgan were at opposite sides of the political spectrum of the day, and they had a deep distaste for one another. In spite of this, with the magnitude of the problems at hand, Morgan contacted George Cortelyou, the nation’s Secretary of the Treasury.

Cortelyou did not achieve his lofty post by being a luminary in the world of international finance. Instead, he had ascended, administration by administration, to successively senior posts almost by happenstance. He started as a stenographer, and President Grover Cleveland brought him into his service based on Cortelyou’s stellar shorthand skills.

He was later the private secretary to McKinley and, later, when the Department of Commerce was formed in 1903, he was given the secretary position of that department. Subsequent President Teddy Roosevelt made him Postmaster General of the country and then, curiously, he was given the position of Secretary of the Treasury. This is where he found himself in the midst of the crisis.

So, at Morgan’s urging, Cortelyou boarded the 4 p.m. train from Washington to New York. Awaiting him in uptown Manhattan was a suite Morgan had prepared as a meeting place for Cortelyou and a retinue of the city’s bankers. The basis for the meeting was to retain the federal government’s aid in yet another looming crisis in the form of the Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company (TC&I).

One of the largest brokerage firms in the country, Moore & Schley, had borrowed excessively during the crisis, and the collateral used for the loans was their substantial holdings of TC&I stock. The stock itself had been weakening through the crisis, and the weaker it got, the more at-risk Moore & Schley became of their loans being called away based on the deteriorating conditions of their collateral.

Such a move would bring the brokerage to ruin and make a severe situation even worse. If the loans were called, Moore & Schley would have to liquidate their TC&I position swiftly, which would not only crush the stock but cause extensive collateral damage to other issues in the market as well.

J.P. Morgan concocted a plan that would not only stave off such a situation but benefit his own financial empire as well. His plan was that the U.S. Steel Corporation (which itself was formed by Morgan via a merger of Andrew Carnegie’s and Elbert Gary’s steel empires) would acquire TC&I at a price of $90 per share. This would be, in itself, a positive acquisition for U.S. Steel, and it would eliminate the risk of Moore & Schley’s prospective collapse worsening the financial contagion.

The problem, of course, was that in the current anti-trust environment, a firm with a 60% market share (namely, U.S. Steel) was not in a position to legally acquire a smaller outfit. Thus, Morgan needed the blessing of the President of the United States for the deal to be permitted. He needed an exception, but given the crisis, his chances were good.

At the same time, the situation with runs on banks and trust companies had not abated, and one firm in particular – the Trust Company of America – seemed to be the next domino likely to fall. Morgan gathered 120 of the city’s bankers and business leaders into his well-used library to get an update on the status of the trust companies in the city.

Morgan told the men that they needed to come up with a solution to the problem, and he left the library to attend to other matters. Only later did the bankers realize that Morgan had literally locked them inside the library, and he intended to keep the key inside his pocket until the men came up with a solution to the mess. They were trapped there and, at Morgan’s behest, had to figure out a solution.

When Morgan entered the room some time later, no consensus had been reached, so he told the men that they needed to come up with $25 million to shore up the trust companies through the crisis or else the city would face unmanageable panic. After considerable prodding, Morgan was able to persuade the de facto leader of the group to sign an agreement to advance the funds, and the rest of the men followed suit. The agreement having been reached, Morgan produced the key and allowed the bankers to return to their homes at 4:45 that Sunday morning.

Cortelyou had finally arrived in New York, and the suite at the Manhattan Hotel uptown was crowded with some of the top finance men of the city representing such esteemed family names as Rockefeller and Frick.

There was not much in the way of financial aid the Treasury could offer directly – its own coffers had a mere $5 million at hand – but the city’s financiers needed the stated support of the Roosevelt administration with respect to stemming the crisis as well as permitting the TC&I sale to proceed.

Two of the bankers, Frick and Gary, got on an overnight train Sunday evening to have an emergency meeting with Roosevelt. Roosevelt’s secretary denied them access to the President, but, by way of the Secretary of the Interior, they were finally granted an audience.

Frick and Gary told the President that, in spite of the prohibitions of the Sherman Antitrust Act, if he did not permit the acquisition of TC&I by U.S. Steel, the financial markets would enter a free-fall. With only an hour left until the market opened, they beseeched the President to make an exception for the good of the country’s financial stability. Roosevelt assented to the exception, and the news received in New York was greeted with great relief.

Jekyll Island

Through the entire crisis, the one man in the middle was clearly J.P. Morgan. Without a central bank to turn to, the financial industry relied on Morgan’s financial resources, connections, public pronouncements, and force of will to steer the collective ship through the storm.

Although the bankers of the city, and the populace in general, were grateful for Morgan’s support and leadership, it had become apparent afterward that relying on a single wealthy individual to shore up the collective financial health of the nation put the country in a vulnerable position. After all, Morgan could have abused the situation even more than he had.

The next year, in May of 1908, Congress passed the Aldrich-Vreeland Act to establish the National Monetary Commission. Its purpose was to investigate the causes of the panic from the prior year and explore ways to prevent such a panic happening in the future. The chairman of the committee (and one of its namesakes) Senator Nelson Aldrich went to Europe – a continent replete with central banks in each nation – to study their system for nearly two years.

It became clear to him there were significant benefits to having a central bank. The series of problems that took place during the crisis of the prior year could largely be attributed to a lack of credit. Without a central bank to turn to, the city’s banks had to rely on the deep pockets of Morgan and his associates. Time and again, Morgan had to either come up with the cash or compel others to do the same, and having an industry rely on its own internal resources – particularly when its health affected the health of the economy as a whole – seemed short-sighted.

On his return in November 1910, Aldrich assembled a meeting under the most secret circumstances at the Jekyll Island Club, located off the Georgia coast. In attendance were senior administrators from the Treasury Department and representatives from the National City Bank of New York, J.P. Morgan, the First National Bank of New York, and Kuhn, Loeb & Company. As Forbes magazine related several years later:

“Picture a party of the nation’s greatest bankers stealing out of New York on a private railroad car under cover of darkness, stealthily riding hundreds of miles South, embarking on a mysterious launch, sneaking onto a island deserted by all but a few servants, living there a full week under such rigid secretary that the names of not one of them was once mention, lest the servants learn the identity and disclose to the world this strangest, most secret expedition in the history of American finance.”

The men decided the best course of action was for the United States to form its own central bank, with the banks themselves holding key spots on its committees. The National Monetary Commission submitted and published its final report in January of 1911, and its recommendations were debated for a full two years. Finally, on December 23, 1913, Congress passed the Federal Reserve Act, which President Woodrow Wilson signed on the very same day, and the Federal Reserve System was thus formed.

Ironically, or perhaps appropriately, J.P. Morgan himself died the same year, on March 31, 1913. It marked the end of one era – – that of outsized personalities dominating the relatively shaky, clubby world of banking – – and the beginning of a new one – – embodied in the form of the Federal Reserve Bank.

The United States had finally joined most of the rest of the industrialized world in the age of modern finance, and even a century later the value and objectivity of the nation’s central bank would be called into question. The tight connections between the banking industry itself and Washington D.C. in the form of the federal reserve system would not always sit well with the public, but there is no doubt that the presence of the central bank tamped down the prospects of more financial crisis springing up on a regular basis, as they had so many times during the prior century.