“Don’t let the gars nibble your toes, Tim!” One of my older brothers knew it was easy to freak me out, since there was no way you could see what was going on beneath the surface of the water. I knew there probably weren’t gars, and if there were, they probably had better things to do than nibble on a little kid’s toes, but it was enough to make me curl all ten of them up, just to be safe.

In my adult life, I have a pretty good idea what a “lake” means to me. It runs along the lines of Lake Tahoe, straddling California and Nevada, or even better, something like a destination from a wedding anniversary I had years ago, Lake Louise in Canada.

As a child, though, there were only two lakes in my universe: one was Lake Pontchartrain, the huge body of water carved into the southeastern portion of Louisiana near where I was growing up, and the second was Lake Mary, where my aunt and uncle had a vacation house.

I’ve written about them before, because in my writings about wealth distribution, I’ve used my Uncle Charles as an example of the prosperity of the middle class, which was in its waning days in the 1970s. Uncle Charles worked at a paper mill in rural Louisiana. These days, given that description, you might expect him to be an opioid addict, barely scrapping by, but in those days, he owned a nice house, had a family, and had a vacation home just as big as his regular house. Hard to imagine, isn’t it?

My favorite part of each summer was being invited to Camp Mary to stay with them for a while. As a kid, I got in a car, was driven for about an hour, and bang, there I was at Lake Mary. It occurred to me a few days ago that I actually had no idea where this place even existed. After all these decades, I never bothered to even look up where this “Lake Mary” was, so I jumped into Google Maps and honed in on it.

I was instantly disappointed. This………..this oxbow morsel……….was the home of so many happy childhood memories? As you can see, Lake Mary was nothing more than a fragment of the Mississippi River that had been abandoned decades ago by the meandering waters. Unlike, say, Lake Louise, which had been carved out of granite eons ago by massive glaciers, Lake Mary was little better than if God himself had taken a deity-sized ice cream scoop, hacked out a backwards letter “C” in the soil, and let rainwater fill it. An old photo I have from Uncle Charles’ cabin confirms this:

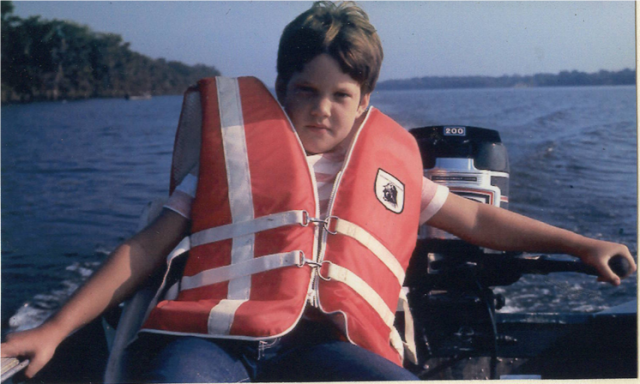

Yet at the same time, it was persistently one of the highlights of my childhood. The rickety dock pictured above was my sidewalk to the water, and although its temperature was nothing better than whatever the sun could manage to muster, the murky remnants of the Mississippi never failed to invoke a plunge and a swim, including a mile-long one I did in order to earn a Boy Scouts badge.

Lazing away the summer by splashing around was a sharp contrast to my life at home, pleasant as it was. I found a photo my parents had taken of my bedroom when I was a little kid, and it was amusing to me (and a bit of a relief, really) to see my habit of being completely tidy and hung-up on order wasn’t an adolescent metamorphosis. Instead, I was the same way as a nine year old as I am now. See how those two pens on my desk form a perfect triangle and meet at a point? That wasn’t an accident. For me, it was a requirement.

There was one particular memory which stood out for me. There was a log jammed deep into the silt at the bottom of the lake. I knew what it was like down there, since I would dive down to the bottom, where the water got much colder, and feel the fine, muddy silt with my feet and hands.

Far from the dock, a few feet of the old tree stuck out. The old tree itself was probably thirty feet long, but almost all of it was under the surface, and at an angle. This was an alluring destination, because large clumps of green moss could be gathered from the moist wood, perfect for hurling at the bare backs of my siblings, creating a satisfying “splat” when it met its target.

When I reached the log, instead of just grabbing some slime from it, I climbed on top of it and took in the view. It was nice not to have to paddle to stay afloat anymore. After a short while, I began to notice something strange going on. Slowly, almost imperceptibly, the water was rising.

It was an eerie sensation. The entirety of the lake – – however many millions of gallons of it there were – – was getting deeper. The water’s surface was crawling higher up my body. What was going to happen to the cabin? Would it be flooded? More immediately, what was going to happen to me? I was going to be underwater in a few moments!

Just before my face sank under the surface, I decided that even if the lake was rising, I could swim my way to safety. So I pushed off the log with my feet and started heading back toward the dock.

As I looked back, the log, which only moments ago had been invisible beneath the muddy lake, slowly pushed its way up again. I stopped swimming, treading water to watch this phenomenon. Suddenly animated, this log lifted itself back up to its original position. All was as it had been before. By sitting on it, I had caused the old tree to start pressing itself into the fine silt, making me think the water was rising when, in fact, I was merely sinking. It was an illusion, but an incredibly vivid one.

A childhood lesson in relative perception, I suppose. It’s probably best not to examine these things too closely. Lake Mary was never going to be a Lake Louise. But from the perspective of a nine year old, every day I had there was magical and mysterious. And, in the mind of a little boy, I watched the waters rise around me with a sense that the world was changing in a way I could scarcely believe, even for a few moments.